Wild emu at the edge of the New South Wales Outback (TWC).

Gifts of bread

Aboriginal stories credit Captain James Cook with bringing bread to Australia. The stories tell about all of things that the mythical "Cook" brought: clothes, axes, animals, and bread and flour. Even though few tribes encountered him in person, they still have Cook tales. The Rembarrnga people of Arnhem Land, where he never ventured, tell of the "real" Captain Cook, their ancestor law-man from millions of years ago. When that Captain Cook is killed, the story teller says that people tried to make him another way, and many "Captain Cooks" (i.e., white settlers) arrived.

Captain Cook statue in Sydney, Australia (March 4, 2018) (TWC)

Chloe Grant and Rosie Runaway of Queensland tell a second story of Cook's arrival bearing bread: "Captain Cook and his group seemed to stand up out of the sea with the white skin of ancestral spirits, returning to their descendants. Captain Cook arrived first offering a pipe and tobacco to smoke (which was dismissed as a 'burning thing... stuck in his mouth'), then boiling a billy of tea (which was dismissed as scalding 'dirty water'), next baking flour on the coals (which was rejected as smelling 'stale' and thrown away untasted), finally boiling beef (which smelled well, and tasted okay, once the salty skin was wiped off). Captain Cook and group then left, sailing away to the north, leaving Chloe Grant and Rosie Runaway's predecessors "beating the ground with their fists, fearfully sorry to see the spirits of their ancestors depart in this way."

Growing wheat

The English soon returned to Australia in force. In 1788, England now bereft of American colonies to which it could ship criminals, landed a boatload of convicts at Botany Bay (Sydney). Within a few months of their arrival, the prisoners turned farmers began to grow wheat. It took several years of hunger while they learned how to farm, found decent soil, and tried planting new varieties of grain, but by 1799, the colony cultivated 6,000 acres of wheat.

A harvested field in New South Wales, February 2018 (TWC).

As was the case around the world, wheat culture in Australia evolved significantly during the 19th century. Early Australian farmers trying to clear ground and plant wheat lacked any sort of sophisticated equipment. Until the first plows arrived in 1797, the convicts and settlers used hoes and spades. The farmable areas near the coasts of the continent were forested, and often hilly. After cutting the trees, farmers hitched teams of oxen to wooden plows. An innovative farmer by the name of Mullens drove spikes into a V-shaped log, which his horse dragged along the plowed soil. The cultivator loosened the dirt and dropped the seeds in behind it. Iron plows didn't arrive until the 1850s.

A few years later, the Australian government paid Richard Bruyer Smith 500 pounds sterling for his invention of the "stump-jump" plow. Smith's plow went along as usual until it came to a stump or rock, at which point a hinge mechanism allowed the share and mould board to lift over the obstacle and come down on the other side. A new Australian wheat variety, "Federation," greatly increased production after 1903 when it was first marketed. New seeds, new machines, and the networks of railroads that were largely in place by the 1880s made wheat farming possible on a large scale.

Wheat sheaves, around 1884 - 1917, Sydney, Australia.

Cooking and eating wheat

During the second half of the 1800s, English in Australia might well have turned to Eliza Acton's The English Bread Book for their bread recipes.

The English and other settlers adapted to their new environs. Occasionally they ate indigenous foods prepared in the same ways that the Aboriginals were accustomed to use them. Far more often than not, they substituted local foods in their own recipes because they couldn't get the ingredients that they usually ate. They cooked parrots instead of pigeons into soups, and prepared kangaroo meat as if it was beef or mutton. Mrs. Lance Rawson's Antipodean Cookbook from 1895 gave recipes for flying fox (tastes like pork), bandicoots, and iguanas (tastes like chicken), preparing them all using English techniques and seasonings.

Flying fox, Sydney Centennial Parklands, 2/10/2018 [TWC]

The indigenous peoples also adapted. They continued to prepare their traditional foods, often using English ingredients -- flour, sugar, the new meats such as mutton, beef, and pork -- to make their traditional dishes. More often, they substituted English foods for their own. The English foods tasted better to them, were far easier to get, and were recommended (or at times, required) by the English who ruled over them. Some English paid indigenous people who were working for them in English foods, including flour.

That's one part of the story. In addition, it's also true that the English brought domesticated animals such as sheep and cattle and sent them out to graze on the Aboriginal lands. Some of the grazed areas had been fields of murnong (yam-daisy tubers) that the Aboriginals managed by judicious use of fire to keep down pests and fertilize the soil. The English took over the grain fields and grass lands that the Aboriginals cultivated and used them for their own crops. Because many of the Aboriginal populations were decimated by Old World diseases, or by deliberate killings, they didn't have the ability to resist, or to continue to cultivate their own foods. English foods were all that were available in many places.

Damper

Classic damper, cooked in campfire ashes (which would be brushed off before eating) [From 2012, in Yandeyarra, Wendy Wood)]

A 1946 recipe emphasized the kneading process for damper, which is strikingly different from hardtack. "Take 1 lb of flour, water and a pinch of salt. Mix it into a stiff dough and knead for at least one hour, not continuously, but the longer it is kneaded the better the damper. Press with the hands into a flat cake and cook it in at least a foot of hot ashes" (Bill Beatty, in the Sydney Morning Herald). Hard tack or ship's biscuit is not kneaded, merely mixed until the dough holds together, then flattened very thin, and baked for a long time at a low temperature until it dries out completely.

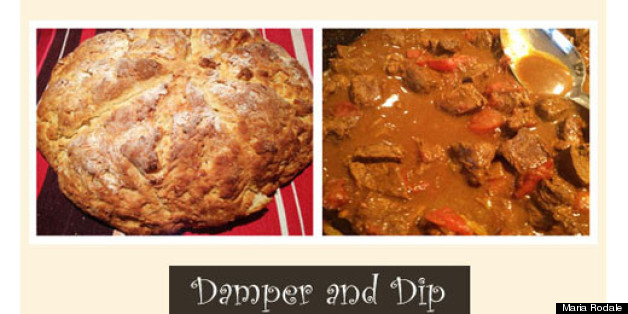

The Aboriginals claimed damper as their own as well. Before the English arrived, they made flatbreads by grinding Spinifex seeds, miller, Kangaroo grass, Bunya nuts, cattail tubers, and other local plants. mixing them with water, and baking the dough in ashes of a campfire. Today, as is shown in the next post, ground seeds and nuts are often mixed with wheat flour to take advantage of the fact that it has gluten and thus will rise when leavened. In a bit of reverse cultural appropriation, the English version of damper is sometimes credited to the Aboriginals, as in this snack characterized as "Damper and Dip: An Aboriginal Tradition."

Australian damper with kangaroo (buffalo can be used instead) curry dip, Maria Rodale

The next post describes wheat in Australia's present, from damper to ramen to Aussie pies. The first post in the series is Who Invented Bread? at this link.