Image of Saint Roch, with the dog bringing bread

August 16 is the feast day of St. Roch (also known as St. Rocco, or St. Rollox), a patron saint of dogs. He was born into French nobility in 1295, but orphaned at 20. He gave away his money to become a pilgrim, wandering through the countryside. Arriving in towns near Rome that were afflicted by the plague, he stayed there to help the sick. After several years curing people and whole towns in the area through his prayers, he caught the plague himself, and went into the forest to die. A count’s hunting dog (assumed to be a greyhound) found him, and brought bread from his owner to St. Roch. St. Roch believed that his guardian angel brought the dog to him, and showed the dog how to heal him by licking his wounds. Paintings of the saint portray him in pilgrim’s robes with a dog by his side carrying bread in its mouth.

After St. Roch recovered, the count, who had become his friend and student, gave the dog to St. Roch. The pair traveled back to Montpelier, France. Arrested as a spy during a civil war in the area, the saint and the greyhound spent five years in jail. Some say that he was cared for by an angel in jail, and some say that he and the dog ministered to other prisoners. Both could be true, of course. He died in jail in 1327.

These dates might not be precise. A Dominican priest and archbishop, Blessed Jacobus de Varagine, Archbishop of Genoa, wrote one of the best known saints' books of the medieval times. He published the Golden Legend in 1295, and included a detailed account of St. Roch, who (in theory) would still have been alive at the time.

How Saint Roch's dog also became a saint to some

Image of St. Guinefort, the holy greyhound

This is not the end of the story. The dog, named Guinefort, lived on, and became part of another noble family. One day the family went out leaving the baby, a nurse, and Guinefort. When the nurse was in another room, a serpent approached the baby, but Guinefort killed it, leaving a fair amount of gore around. When the family returned they saw the blood, thought that Guinefort had harmed the infant, and killed the dog. But then, on closer look, they saw the snake and realized their mistake.

The nobleman buried Guinefort in a well, and planted trees to mark the grave. Local women began bringing their babies to the site, praying to the dog for protection. In days past, the same peasants had made offerings to the fauns and spirits in the area; now they brought their children's clothes and lit candles as ritual offerings. Despite numerous criticisms and attempts to quash the beliefs, a historian passing through the area noted that it was still practiced after World War 1. "Saint" Guinefort even has his own day, August 22. The Catholic Church certainly does not consider Guinefort a saint, but many people appreciate the story and sentiment and continue to tell it.

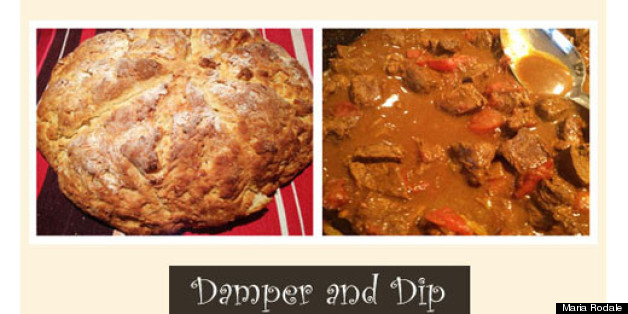

Dogs and bread

Fire Island bread cooling on rack [photo by TWC, July 29, 2018]

The association of the dog with bread might seem accidental, but in fact it is likely that we owe our friendship with dogs to the fact that they developed a love of wheat when people began to plant it 11,000 or so years ago. One of the most important ways in which dogs differ from their ancestors, the wolves, is their ability to thrive on grains. To do this, dogs evolved genes that increased their starch-digesting enzymes. Human digestive systems also developed more of these genes and enzymes at about the same time. The Nature article that described the genetic research concluded, “The results presented here demonstrate a striking case of parallel evolution whereby the benefits of coping with an increasingly starch-rich diet during the agricultural revolution caused similar adaptive responses [i.e., new ability to digest starches from grains] in dog and humans.” So wheat may be a crucial part of the process that gave us not only the food of life, but our best friends in the animal kingdom. Although other theories about how dogs joined their fates to humans exist, evidence supports the wheat theory, and the other theories are not mutually exclusive.

The American Kennel Club advises that it's still OK to feed your dog certain kinds of bread, in moderation. No raw bread dough, however, and no bread with raisins (raisins are toxic) or some sorts of nuts (especially macadamia), some brands of peanut butter, and no Xylitol.

Mom Oreo advises her young daughter on how to catch the tastiest dinners and invite your humans to provide some tasty bread [photo, Micki Glueckert, July 28, 2018].

My thanks to Barbara Armstrong, a dog lover who told me about St. Roch, and the dog who brought his bread.